The First Europeans (1542 to 1850)

Early Coastal Exploration

Fifty years after the discovery of the Americas by Columbus, an expedition was sent from Mexico to explore the Pacific coast by sailing ship. In 1542, Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo sailed from Baja California exploring the coast line to the north. This was 80 years before the Pilgrims settled in New England and 227 years before the California missions were established.

^ ^ ^ Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo (1497–1543) the first European to navigate the coast of present-day California.

Cabrillo entered the Santa Barbara Channel on October 7, 1542. Three days later, the ship visited the mainland, possibly near the mouth of the Santa Clara River (Ventura). Cabrillo continued along the coast, and on November 11 sailed around a point he named Cabo de Galera (Point Conception). This trip carried him as far north as Bodega Bay (north of San Francisco).

The expedition returned to San Miguel Island by November 23, where the party wintered. During the winter stop over, Cabrillo died. He had instructed his officers to continue the exploration of the coast, and on February 18 they sailed north again as far as Cape Mendocino before sailing back to Baja California.

Cabrillo's exploration of San Diego Bay was to have special significance. Based on his reports, this site was later chosen as the first permanent Spanish settlement in California established in 1769.

Settling California

Despite more than two centuries of coastal exploration, there were no attempts at colonization in present-day California until the Spanish established the first permanent settlement at San Diego in 1769, and soon afterward at Monterey.

Fear of Russian expansion from the north convinced the Spanish colonizers in Mexico to expand their growing empire into California Nueva (New California). The 1768 Russian naval expedition of Pyotr Krenitsyn and Mikhail Levashev had particularly alarmed the Spanish government. In that same year, King Carlos III of Spain issued an order to settle the lands to the north to block Russian expansion. The Visitador-Generál of New Spain, José de Gálvez, entrusted Portolá with the vital mission of securing all of California for the Spanish Empire. They organized a plan of occupation under the overall command of Governor Portolá.

The next year, Portolá commanded combined land and sea expeditions that extended Spain's control up the Pacific coast by establishing the first settlements and missions in present-day California.

Two supply ships, the San Carlos and San Antonio, sailed north from La Paz, in Baja California, and arrived in San Diego Bay in April 1769. The San Carlos arrived later than expected on April 29 with scurvy-ridden troops. They had sailed over 200 miles off course due to cartography errors.

Meanwhile, two land parties, one commanded by Rivera y Moncada accompanied Father Juan Crespi, and the other under Portolá's command accompanied by Father Junípero Serra, set out from Mexico on foot and on horse back. The Rivera party went ahead to open the trail. They reached San Diego in May, and Portolá's party arrived in late June.

Although food was critically short and many of the men were ill, Portolá did not delay in setting out with sixty-four men to search for the reported harbor of Monterey further north. Father Junípero Serra remained in San Diego to oversee the first rudimentary settlement in California Nueva (New California). The territory California Nueva was later renamed Alta California (Upper California).

Portolá left on July 14, 1769, with Fathers Juan Crespi and Francisco Gomez, a sergeant, an engineer and 32 soldiers, as well as some Indians brought up from Baja California. As they traveled north from San Diego, Portolá looked for possible mission sites.

Just two weeks into their journey, the expedition was rocked by an estimated magnitude 6 earthquake while camping near Santa Ana on July 28, 1769. This event is the first earthquake to be documented in California's historical record.

On 8 August 1769, Portolá's expedition passed through the Santa Clarita Valley, crossing at Elsmere Canyon. On this day, the party felt a major aftershock following the earthquake 11 days earlier. On August 11, they camped at Chaguayabit (Castaic Junction), before heading down the Santa Clara River Valley to the Pacific Ocean (Ventura).

A Spectacle to Behold

Imagine the unprecedented spectacle of a party of soldiers in eighteenth-century apparel suddenly appearing out of nowhere. The historian, Jerry Reynolds, describes the scene as follows: "Sitting astride his military horse waiting for scouts to return with reports from the field, Don Gaspar de Portolá was a stately figure. He wore an officer's uniform with a blue, tri-cornered hat with gilt edging, light blue coat over a white vest, tight riding pants and knee-length black boots. A pair of flintlock pistols was thrust into his crimson waistband while a saber clattered from his pommel. He was clean-shaven, an inconvenience on the trek perhaps, but a symbol of pride and morale for the troops."

The expedition passed Monterey without recognizing their intended destination and continued further north exploring the area around San Francisco Bay. From there, the expedition returned back to their recently founded settlement in San Diego in late January, 1770.

In the Spring, Portolá returned north again and successfully located Monterey, where he was met by a supply ship which had sailed up the coast from San Diego. The Monterey Presidio was established and not long after Mission San Carlos Borroméo de Carmelo. Portolá's overland route was subsequently known as "El Camino Real." Today, Highway 101 more or less follows Portola's original route.

^ ^ ^ Don Gaspar de Portolá.

Our Neck of the Woods

The first "white men" to visit our mountain abode were Europeans from the Spanish empire. The first documented Spanish presence in the Frazier Mountain area was in 1772 by a military detachment lead by Pedro Fages. This party holds the unique distinction of being the first foreigners to visit our neighborhood from another continent.

^ ^ ^ Pedro Fages was a Spanish soldier and explorer who later was destined to become the second and fifth Governor of Alta California.

In the early years of colonization, Captain Pedro Fages was the commanding officer of the presidio of San Diego, the first Spanish settlement in California. On 29th October, 1772, he commanded a small troop of soldiers that traveled east from the presidio in search of six army deserters who had run away with Indian women.

Following reports from Native Americans they encountered along the way, the chase turned northwards and traveled through the Cajon Pass (now I-15 near San Bernardino). From there they entered the Antelope Valley and crossed the Sierra Pelona mountains arriving in a large, unexplored valley that Fages named Soledad Canyon. They camped in this valley near Agua Dulce Springs, which Fages also named. He named the springs after its supply of arsenic-tainted "sweet water".

Continuing west to the Santa Clara valley, Fages was back on familiar ground. Only a few years earlier, Fages had stood there with Governor Portolá and Father Juan Crespí during the the first land expeditions to Monterey Bay.

After resting for two days, his party climbed up Castaic Canyon following a lead from the local Tataviam Indians who reported seeing white men heading north. They journeyed to a "laguna" known today as Elizabeth Lake. They continued west along the western Antelope Valley to another lake that Fages named Salinas de Cortez. We know this lake today as Castac Lake (or Tejon Lake) which is situated on the Tejon Ranch adjacent to modern-day Lebec.

^ ^ ^ Castac Lake (or Tejon Lake) near Lebec.

From the Lebec area, the Fages expedition descended through Cañada de los Uvas (Grapevine Canyon) naming this route Portezuelo de Cortes (Cortez Pass). We know it today as Tejon Pass. There is a historical marker (#283) alongside Lebec Road commemorating this event.

The expedition went on to explore the southern part of the San Joaquin Valley including the Buena Vista Lakes before continuing on to Mission San Luis Obispo. The detachment never found the deserters but the chase lead to the first Spanish exploration of parts of the interior previously unknown to the Spanish. Fages provided the first written record of what has become Kern County.

Pedro Fages was a Spaniard of particular notoriety in his day. Fages's nickname was The Bear bestowed upon him while hunting wild bear near San Luis Obispo. He was also an important military figure becoming a full Colonel in 1789. Later Pedro Fages was appointed the governor of the new California, not once but twice.

Fages was in military command of the ship, San Carlos, on its voyage as part of the first expedition that settled San Diego Bay. Fages had also accompanied the famed 1769 and 1770 Portolá land expeditions to locate Monterey Bay. When Governor Portolá left Monterey, Fages became the new governor of California from 1770-1774. Fages was again appointed the Governor of Las Californias between 1782 and 1791, replacing Felipe de Neve (who is credited with founding Los Angeles).

Approach from the East

Another significant visitor to our local area was Father Francisco Garcés in 1776. Father Garcés was another remarkable Spanish figure; not from the military like Fages but from the Church.

^ ^ ^ Father Francisco Garcés.

While stationed with the Yuma Indians on the Colorado River, Father Garcés became intrigued by the extensive trading routes that the Indians had developed across the Mojave Desert. In 1776, Father Garcés set off with four Indians and headed towards the area of modern-day Needles (on I-40). After crossing the desert, his guides left him near present-day Victorville. Then traveling alone, Father Garcés proceeded over the Cajon Pass (I-15), and headed to the nearest mission, Mission San Gabriel (near present-day Pasadena). His remarkable desert crossing took 24 days.

Two days later, he headed towards the San Fernando Valley following the then established 1769 Portolá trail. He climbed over the Newhall pass and arrived at Rancheria del Corral (at Castaic Junction) in the Santa Clara River Valley. Here Father Garcés encountered a war raging between the Tataviam and the coastal Chumash. He spent ten days in the area during which time he managed to help settle the dispute.

In a diary entry on 22 April 1776, Father Garcés wrote: "I noticed how mild and approachable the people of this (Tataviam) nation are." His recording of the Indian names "Islay" and "Kashtuk" were to evolve to become the place-names Hasley (as in Hasley Canyon) and Castaic.

Garcés then traveled up San Francisquito Canyon to Elizabeth Lake. Here his path coincided with that of the earlier 1772 Fages expedition. Continuing west, he made his way to what is now Castac Lake (or Tejon Lake) near present-day Lebec.

To place this event in a historical context, the explorer Franciscan priest, Francisco Garcés, was in our neighborhood in the same year as the signing of the United States Declaration of Independence.

After this, Father Garcés descended into the San Joaquin Valley, crossed the Kern River, and visited Tulare Lake. He then returned through Tehachapi Pass and followed the Mojave River. He eventually arrived back at the Yuma crossing on the Colorado River, where he spent the next five years.

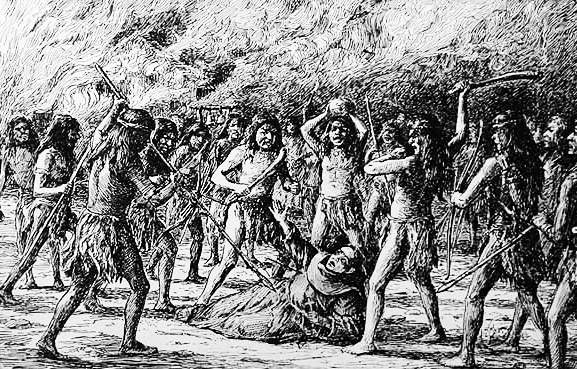

Incensed by the attitude of the soldiers stationed there, the Yuma Indians rose up in a fury and killed every Spaniard in sight. Father Garcés was clubbed to death in a wild frenzy during the famed Yuma Revolt on 19 July 1781.

^ ^ ^ Yuma Revolt in July 1781.

The opening of the route across the Mojave was significant. The safest and most economical route back to Europe was by ship departing from the Gulf of Mexico. The alternative route from the Californian Pacific coast added months to the sea voyage and a dangerous passage around the Cabo de Hornos (Cape Horn) one of the most hazardous shipping routes in the world.

Approach from the West

Spanish knowledge of the interior of California was sketchy during the first decades of coastal settlement. Much of this knowledge was learned from expeditions in search of military deserters and runaway mission neophytes.

On August 24, 1790, Commandante Felipe de Goycochea dispatched a party of nine men, headed by Sergeant Jose Ignacio Olivera and eight soldiers, to search for a neophyte named Domingo who had run away from Mission San Buenaventura. They quickly located Domingo at the rancheria of Tinoqui.

Goycochea had also ordered the dispatch to search for mineral deposits reported to be in San Emigdio Creek. So the party proceeded to this area to carry out this second phase of their mission. They set up camp at a place called Cullamuhuasulugoy. On August 29, Sergeant Olivera detached a party of five men to broaden the search. Sergeant Olivera and three soldiers remained in camp. Later the Sergeant took one of the men with him to make a reconnaissance of another area. This left just two soldiers to guard the camp.

Tragedy Strikes

Meanwhile, a disgruntled group of about 58 Indians were planning a raid on rancheria of Najalayegua. When they came across signs of the Olivera party in San Emigdio Canyon, they located their camp and stealthy attacked. Gabriel Espinosa was sleeping and met death without awakening. Hilario Carlon, the guard on watch, was sewing his shoe. He was killed by a knife thrust seeming to appear from nowhere.

Later, the five soldiers dispatched earlier returned to find their dead companions. They buried the unfortunate pair and started back to Santa Barbara. On the way they were surprised to run into Olivera and the other soldier, as they thought they had also been killed by the Indians. The group arrived back in Santa Barbara on September 1st.

A party of 28 soldiers and Sergeant Olivera under the command of Alferez Pablo Cota was dispatched to bring back the Indians who had perpetrated the attack on the soldiers. The Indians had advanced warning of Cota's approach and the villages were vacated by the time the soldiers arrived. However, they did manage to capture two prisoners, Soxollue of Taxicoo, who had taken part in the fatal attack.

The Spanish had learned a valuable lesson in San Emigdio Canyon but at the cost of lives lost. Later expeditions into the interior were rarely surprised by Indian attacks as small detachments of men were no longer split up in potentially dangerous situations.

Further Visits

On August 28, 1795, a Spanish exploration party from San Fernando Mission traveled north crossing the difficult mountainous terrain to successfully reach Castac Lake at Lebec (not to be confused with modern Castaic Lake further south).

Another expedition to the greater Frazier Mountain area took place in 1806. The expedition was carried out at the governor's direction in an official letter dated July 10, 1806. Father Jose Maria de Zalvidea and his party set out from the Santa Barbara Mission on July 19. By July 22, they had descended into the Cuyama Valley. From there they headed north to the villages of Buenavista and Sisupistu on Kern Lake. After visiting other villages on the Kern River, they headed south. On August 4, they entered San Emigdio Canyon where the Olivera party had been attacked in 1790.

They continued on to Mill Potrero and traveled down Cuddy Valley. On August 6, they camped by a sag pond on the San Andreas Fault in the vicinity of Gorman. The next day, they made a side trip to the village of Casteque located near Castac Lake (now part of Tejon Ranch in the Lebec area). After this they traveled east along the Antelope Valley and reached Mission San Gabriel on August 14.

Father Zalvidea's report of the trip to the governor gave the location of Indian villages with estimates of the number of individuals living in each one. The report also described the vegetation and water resources of the areas they passed through.

Spanish Mining

Then came an era of secret Spanish mining right in our own "backyards". The legend of the Lost Los Padres Mine begins.

The newly arriving Spanish priests started to mine silver and gold in areas associated with what we now call the "big bend" of the San Andreas Fault where rich deposits had been exposed by plate shifting and fault activity over the eons.

A partnership, of sorts, was entered into with the local Native American tribes. With their intimate knowledge of The Land, the Indians were able to pin point mineral outcroppings that might interest the Spanish. With the Native Americans providing the manual labor, the Spanish started mining in earnest.

The mining continued for several decades leaving us with several legends relating to the "Los Padres Mine". Spanish and Mexican mining was brought to an untimely end for political reasons by the inescapable consequences of the series of events leading up to the Mexican-American War (1846 to 1848).

With the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican-American War, California became the thirty-first state of the Union in 1850.

![]()

Peter Gray

telephone: +1 (661) 242-1234